Rupert Zallmann:

Techo en México is not just a structure; it is a sanctuary of community, a beacon rising from the heart of the land, designed to gather rain from the heavens and embody a symbol of hope and resilience. Dedicated to the Tonantzin Tlalli Institute, this space stands as a testament to the harmony between humanity and the earth. The institute, a demonstration center for ecological agriculture and alternative technology, is nestled in Paraje Bonanza, in the rugged beauty of Ejutla, Oaxaca.

Under the unrelenting Mexican sun, the design, organization, fundraising, and construction of this space became an act of devotion. Each day unfolded as a blend of sweat, dust, and ambition, with nights spent sleeping on the bare ground, beside buckets of Mezcal, surrounded by the vast silence of nowhere. A labor of love, shaped by hands, hearts, and minds.

The key protagonists of this project were Dominik Brandis, Jean Pierre Martinez Bolivar, Alex Matl, Giulio Polita (author of the initial design), Rüdiger Suppin, Florian Schafschetzy, and Rupert Zallmann, students from Studio Prix at the Institute of Architecture, University of Applied Arts in Vienna. Enabled and inspired by their mentor, renowned architect Wolf D. Prix, co-founder of the avant-garde studio COOP HIMMELB(L)AU, they brought to life a creation that now stands proudly on a hill, overlooking the valley below.

But it was more than a student's experiment; it was a collaboration steeped in spirit and soul. With the invaluable guidance of Bärbel Müller and the support of Franz Sam, Reiner Zettl, Peter Strasser, Andrea Börner, and Martin Hess, this project evolved into a structure that both respects and exalts the land upon which it stands—a structure that, like the ancient temples of Oaxaca, holds within it the spirit of the earth and the dreams of the people.

Here, in this space, Techo en México becomes more than a shelter. It is a living symbol of resistance and renewal, a reminder that even in the harshest of conditions, creation can flourish. It gathers rain and life, channeling it into the parched earth, giving back what the land offers, while its presence in the landscape serves as a quiet but bold reminder of the timeless connection between, nature, and community.

This edifice, born from struggle and dedication, stands to be remembered. In its simplicity and strength, it speaks of a future where we once again learn to live in balance with our world.

Raimund Abraham:

Immutable Velocity

About ten years ago, on my way to Dainzu, a remote temple site in the Tacoluca Valley, between the City of Oaxaca and Mitla, diagonally across from Yagul, I encountered a two-wheeled, oxen-drawn cart, overloaded with maize. It was heavy and, as it appeared to me, motionless. The wheels towered twice the height of the peasant, who seemed petrified in his walk.

In that moment, I realized that the power of the wheel does not lie in its propulsion, but in the negation of its motion, frozen in the timeless moment of its invention.

Progress, all novelty, is marked by nothing more than the attempt to reinvent, within fragmentary cycles, the inventions of the ancients. This ruptures the limits of immutable structures through the denial of motion while intensifying all space in the cessation of somatic time.

Architecture-time is labor-time, measurable only during the process of construction, either to dissolve into the dot-zero of entropic space or to condense into infinity.

At San José Pacifico, a magical place of magic mushrooms, after crossing the Sierra—the mountain range stretching along the Pacific Ocean—the great plains of Oaxaca emerge: the Etla Valley to the north, the Tacoluca Valley to the east, and Valle Grande to the south.

A landscape of unexplored spaces: rugged mountains, hills like red-earth elephants, wide fields of agave, and dense bamboo shielding the riverbanks of the Rio Atoyac.

On significant vertices of the landscape, surveyed through the eyes of astronomers, the Toltecs and Mixtecs built their temple mounds. The idea that students from the "Angewandte" in Vienna, in accepting the challenge, could erect an edifice that would respect and dignify the spirit of this mysterious land carried my doubts from the start.

Not impossible, I thought, but improbable.

The edifice is intended to collect and distribute rainwater, and provide shade for transient inhabitants. A body, anchored in the bone-dry earth, awaiting the rain as a silent witness in the cycle of the seasons.

One leaves the paved road on the way back to Mihuatlan, about thirty kilometers outside the City of Oaxaca near the village of Ocotlan, at the mercilessly normal setting of an electric power plant.

At first, a narrow path with wind-blown, spiraling dust clouds, then only wheel tracks of unknown origins through steep, winding, fissured hills. Finally, the eyes are torn from the landscape, capturing the view of the edifice, suddenly and surprisingly.

In the void of barren hills, sucked dry by an unrelenting sun, a bamboo cloud with counterweights—a “Wolkenkuckucksheim,” according to Aristophanes—

“A city built by birds in the sky.”

“A city built by birds in the sky.”

The compelling image of the structure demands that you pierce it with your eyes, dissect its parts, probe its suspended weight, and follow the forces of resistance defying the terror of gravity.

“Crevices in the earth, rain on the palm of your hands, and skin stretched over the bones.” (Raoul Schrott)

True construction must question time to comprehend the void of space.

Lines of bamboo, drawn or built. Hollowed grass, lightweight and sturdy, edible during its early growth, at its peak, a weapon against gravity. Halved, dissected, carved, pointed, penetrated by threaded shafts, and connected by nodal junctions.

Suspended crossbars of concrete, resistant to compression, with the entire structure anchored by squared blocks of concrete buried in the earth.

Utmost clarity of construction, carried by a rare poetic vision.

This edifice is new—in the truest sense, new—contrary to the shallow newness of contemporary fashions in architecture.

You succeeded in creating an edifice that not only celebrates resistance but provokes it. Not to be remembered, but to be unforgettable.

Zapata vive!

Klaus Bollinger:

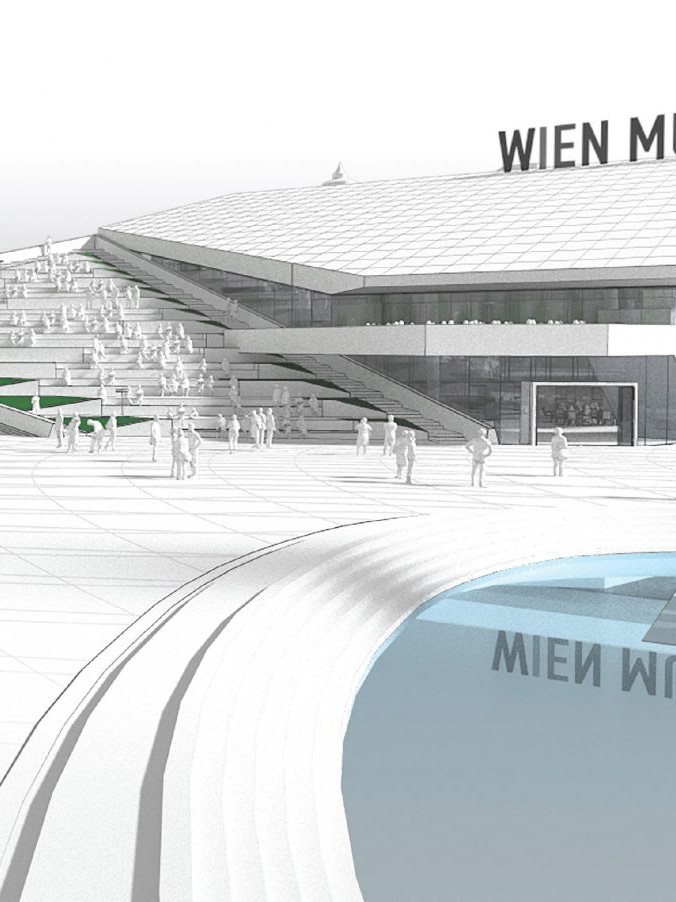

Shell structures provided an initial direction for the Ejutla project, though what was ultimately built is not a shell in the conventional sense. Shells are defined as surface structures with single or double curvature, where their thickness is minimal relative to their surface area. As a result, they primarily experience tension and compression forces; bending moments, if they occur at all, are only secondary phenomena.

In this project, pure shell forms were initially examined. Ideal forms were derived based on the flow of forces by using hanging models. The further development of the design process became an exemplary case of an approach that can be described as "pragmatic structural design without ideology." This approach involves initiating an optimization process that, while considering all initial parameters, may deviate from the textbook ideal structure to achieve overall optimization. Through this process, hybrid structural forms are developed, whose performance is not necessarily inferior to that of a "pure form" structure and that meet all outlined conditions optimally. In this particular case, the roof needed to provide shade, protection from rain, drain water to a cistern, integrate with the surrounding landscape, and, most importantly, serve as an emblematic symbolic sculpture that conveyed lightness and a floating quality.

After the initial exploration of ideal shell forms, which were also tested using hanging models, the design evolved as all project requirements were considered. This led to the dissolution of the ideal forms. The departure from a pure shell form altered the structural performance such that, in addition to axial forces, bending moments were also necessary to transfer the load. To achieve this, an internal lever arm was required, which meant that the building elements needed to have a certain thickness.

Two mesh shells were first constructed in a rigid, triangulated grid, forming two layers, one above the other. These layers were separated to create a two-layer, free-form overall structure. To ensure that the two layers worked together, diagonal connections were required, though they were minimized compared to traditional space frames. These connections consisted mainly of posts that kept the two layers apart or wire cables inside the structure.

When selecting the material, factors such as availability and the feasibility of working with it on-site were considered, alongside ecological aspects that favored sustainable raw materials. Bamboo, a material with high rigidity that can be worked using relatively simple tools, was chosen. The supports were made of hollow steel tubes. The load transfer from the shell to the supports was achieved via ferrocement cross-junctions at the tops of the supports within the shell's interior. Initially, a thin ferrocement covering was proposed for the roof, in continuation of the Mexican tradition of reinforced concrete shells. However, metal sheeting was ultimately chosen to reduce weight and ensure durability, as the different performance characteristics of the materials, along with the possibility that the roof might be walked on (although this was not specifically planned), raised concerns about cracking in the ferrocement.

The result is both impressive and remarkable in many respects. The inductive, experimental process involved in designing and constructing the shell was especially exemplary. The project team did not limit itself to selecting from known typologies. Instead, armed with knowledge of these typologies and motivated by a spirit of inquiry and exploration, the team set out to leave familiar paths behind, constantly seeking new directions, evaluating them, and refining them further.